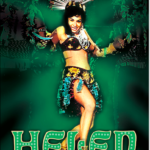

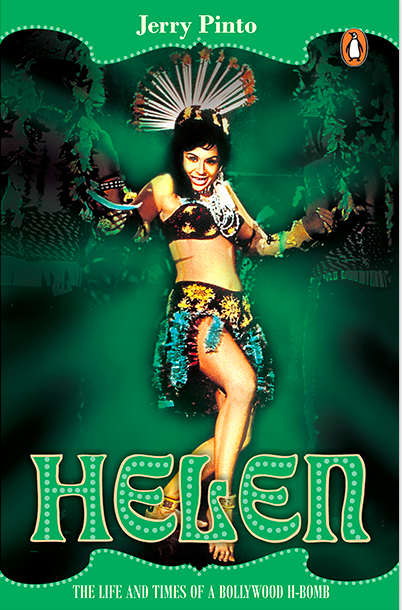

Book Review: Jerry Pinto’s ‘Helen: The Life and Times of a Bollywood H-Bomb’

I won’t go so far as to say that Helen was the first Hindi film actress I remember seeing (that would be Shakila, since CID was the first Hindi film I remember watching). But I distinctly remember being about 10 years old, watching Chitrahaar, and being very excited because an old favorite of mine, a song I had till then only heard and never seen, was going to come on (in Chitrahaar, there would always be a sort of intertitle between songs, a single frame in which the name of the next song, the film it was from, and the names of the music director, the lyricist, and the singer(s) would be listed).

This song was Mera naam Chin Chin Choo, and my feet were already tapping when it began. All that frenetic movement, those men in sailor suits dancing about. The energy, so electric that it even seemed to transmit itself to the musicians. The infectiousness of it all.

Mera naam Chin Chin Choo (Howrah Bridge, 1958) was a fitting introduction to Helen, since it was the song that catapulted her into the realm that she was to rule over for much of the next three decades. It was also, as Jerry Pinto insightfully points out in his book Helen: The Life and Times of a Bollywood H-Bomb, a precursor of things to come. This song was an indication of the space Helen would occupy in Hindi cinema:

Miss Chin-Chin-Choo is an ingénue here more than anything else, offering only a certain physical energy and a bodily charm. She is surrounded by what will later become a standard trope of the Helen figure, a group of male dancers… Her name establishes her alienness… Her use of English establishes her westernization, underlined by the dress she is wearing, the honky-tonk music, and the way she dances with the sailors…

This, the taking of a certain song or scene and analyzing it to draw inferences about a character, or even about tropes in cinema, is one of the main reasons for my liking Pinto’s book a lot. At the very start of the book, Pinto explains that though he tried umpteen times to get hold of Helen, he could not: true to her past history of interactions with the paparazzi or others looking for interviews, she shunned the curiosity. Pinto, therefore, was left to gather whatever meagre information he could get from the rare interview (one in Savvy, for example), in which Helen did condescend to speak about herself.

The personal angle, the biography, is therefore limited. It talks briefly of how Helen was born to a French father and a mother, Marlene, who was half Spanish, half-Burmese. When her husband died, Marlene married again, this time a Britisher named Richardson (whose last name Helen adopted). During World War II, Mr Richardson died, and when the Japanese attacked Burma and occupied it, Marlene, Helen (then three years old), and Helen’s baby brother trekked from Burma into India. They washed up in Bombay, which was where, years later, a 12-year old Helen had to drop out of school and begin learning dance. Later, thanks to the dancer Cuckoo (who played cards with Marlene—or it might have been her parents who played with Marlene), Helen got her first break in films, with Shabistan (1951).

That, barring a passing and non-salacious reference to Helen’s relationship with the film maker PN Arora, followed by her subsequent relationship with (and finally marriage to) Salim Khan, is the extent of Pinto’s discussion of Helen’s personal life.

The rest of this book—nearly all of it—is about the onscreen Helen. Pinto divides this into several chapters, in which he analyzes different aspects of the women Helen played in the several hundred (not likely thousand, as has been quoted at times but which Pinto disagrees with) films in which Helen appeared. He also examines broader aspects of cinema in the process, including tropes, characters, and styles.

For instance, in The Woman Who Could Not Care, Pinto discusses the vamp, beginning with the legendary Theda Bara, and going on to discuss how a newly independent India’s cinema found a counterpoint to the Mother India image in the vamp—and how this implied that the vamp, to be completely and utterly distinct from the pure, traditional, virtuous Indian sati savitri that was exemplified in the heroine, had to be cast as a complete outsider.

Bollywood’s version of the vamp, white-skinned, Westernized, exulting in her own sexuality, the very obvious ‘bad girl’ was exemplified, of course, in Helen, who by virtue of being (in reality, not merely onscreen) part white, Westernized, and unabashedly comfortable with her body, was pretty much made for the part. The rest was added on by film makers. The costumes Helen wore, the songs she lip-synced to, the props that featured in her dances, the way fellow dancers, actors and extras fitted into her dances: all of these (and more) contributed to the Helen persona, as Pinto sets out to show us.

Pinto doesn’t resort to an outright chronological progression of Helen’s films. Instead, each chapter is devoted to a different aspect of the vamp that Helen portrayed. In one chapter, he creates a (sort of) taxonomy of the vamp: the white goddess, the indicator of debauchery (a hero stepping into a space where Helen was dancing automatically indicated to the audience that he was now stepping into a den of vice), the teacher, the moll…

Then, in another chapter, Pinto looks at the different types of songs Helen danced to. Songs of seduction, of course; but also songs of mockery, songs of misdirection, and more.

With each assertion and discussion, Pinto describes scenes and songs galore from Helen’s oeuvre, complete with relevant back stories, quotes of lyrics, and so on, the entire argument coming together to support a theory.

Besides the fact that he’s done a good deal of research into Helen’s films, what I really liked about Pinto’s book is the intelligent and very keen dissection he carries out of the Helen persona. I have seen a lot of Helen films (Pinto provides a filmography—which he admits is not complete—at the end of the book, and I figured I have seen more Helen films than Pinto has), but there were so many things he pointed out here that I’d never noticed.

It’s easy to see how Ruby dying in Teesri Manzil, or Kitty being killed in Gumnaam, or Helen’s character dying in countless other films, is an indication that the vamp is just too bad for redemption (even when she has a heart of gold) —but to find a connection between that and Amitabh Bachchan’s character dying in everything from Sholay to Deewar to Muqaddar ka Sikandar? Now that was something I hadn’t realized. But when Pinto writes about it and explains it, it makes perfect sense.

Similarly, there’s the fascinating discussion about Helen acting as the love interest of comedians—Johnny Walker, Mehmood, Rajendranath, etc—in film after film. I would have thought this was a simple case of a bit of comic relief and a secondary romantic track to balance out the relatively ‘serious’ melodrama of the main track. But no: Pinto dissects this too, and shows, through various examples, how there’s a subliminal message here, aimed at reinforcing the virtues and heroism of the hero and heroine.

And so on and so forth: Pinto examines several other aspects of the vamp that Helen played (even when her character may have been portrayed in a more sympathetic light, as in Woh Kaun Thi? or Pagla Kahin Ka). After tracing her dancing career till it petered out completely in the 1980s, Pinto writes about how Helen reinvented herself in the late 1990s and the early years of the 2000s (this book was published in 2006) as the motherly figure in films like Khamoshi, Mohabbatein, etc. He ends with a bit about how Helen has been paid tributes: by knockoffs in films, by being referenced in (the admittedly rare) films about film-making and the world of cinema. By the thousands who grew up loving Helen and who insist that “there was never anything vulgar about Helen”.

This is not a book you should pick up if all you want to know is the gossip surrounding Helen. In fact, it’s not even a book for those only interested in Helen’s personal life, salacious or no. What it is, is a very good analysis of the onscreen phenomenon that was Helen. It’s very intelligent, incisive and insightful. Plus, Pinto has a good sense of humour, which especially comes into play when talking about some of the more loony B-Grade films Helen appeared in:

Another magician, this time one with evil intent, descends from an extraterrestrial globe that falls out of a cardboard sky, but not before you see the string holding it up for the camera.

My only grouse about this book was that the print quality wasn’t good enough to do justice to the photographs. Not that there are a lot of photographs, but the ones which are there (mostly stills from various Helen films) would have benefited from being printed on better quality paper.

Highly recommended, not just as a book about Helen, but as one about the Hindi cinema of the 50s and 60s too.